In the depths of a brutal Arctic winter in early 1925, a remote Alaskan town faced a crisis that threatened to become a tragedy of devastating scale.

Nome — a small community cut off from the outside world by ice and snow — was confronting the specter of a diphtheria epidemic, an illness deadly especially to children and vulnerable residents.

With the only supplies of lifesaving antitoxin stuck hundreds of miles away in Anchorage, and with aircraft and shipping blocked by severe weather, something extraordinary had to be done.

The solution that emerged would become one of the most legendary feats of endurance and teamwork in history: a dogsled relay across hundreds of miles of hostile terrain.

This mission, known as the Great Serum Run or the Great Race of Mercy, required teams of mushers and sled dogs to relay the lifesaving diphtheria antitoxin from Nenana to Nome — nearly 700 miles in temperatures that plummeted as low as –60°F.

A succession of teams braved blizzards, gale‑force winds, and bone‑chilling darkness, working around the clock in a desperate bid to deliver the medicine in time.

In just about 127 hours — roughly five and a half days — the relay was completed, a performance that would have taken a month under normal conditions.

Among the many courageous sled dogs and mushers who participated in this remarkable effort, Balto became the name most widely known to the public.

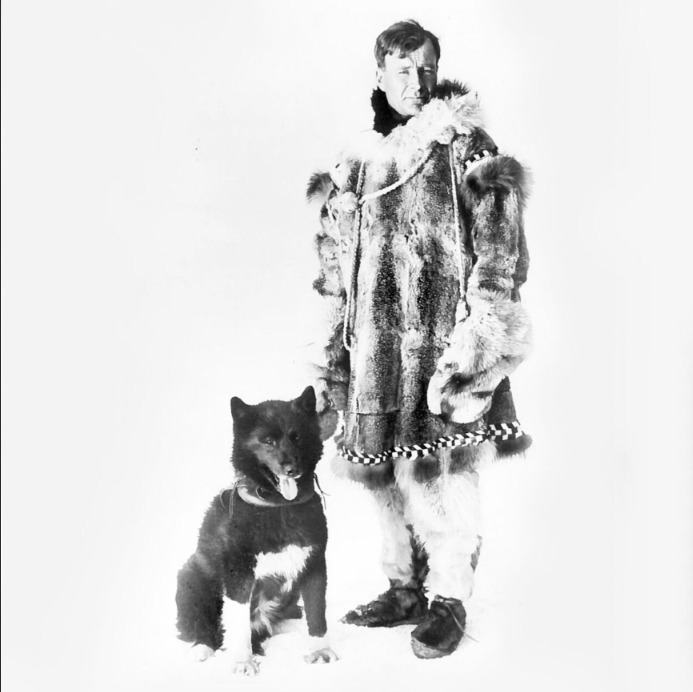

Balto was not originally destined for fame. He was one of the backup dogs in musher Leonhard Seppala’s kennel, seen as more suited for hauling freight than leading a team.

But when fate called, Balto rose to the occasion. On February 2, 1925, he led musher Gunnar Kaasen’s team through chest‑deep snow, disorienting conditions, and fierce winds on the final leg of the journey into Nome.

For Balto and his team, the terrain was treacherous enough that at one point Balto stopped the team abruptly — sensing dangerously thin ice that could have plunged them into icy water.

That instinct likely saved not just the serum but lives.

When Balto and Kaasen arrived in Nome with the precious serum, the town was already bracing for catastrophe.

Instead, they were met with relief and gratitude, as the delivered antitoxin helped to halt the spread of the deadly disease.

Immediately, Balto’s name became synonymous with courage and endurance.

Newspapers across the United States carried his image, and radio broadcasts hailed the dogsled teams as heroes — a remarkable achievement for both humans and animals working in concert.

Balto’s fame extended far beyond the frozen trail.

A bronze statue of him was erected in New York City’s Central Park, becoming a pilgrimage site of sorts for generations of visitors inspired by the story.

Despite his rough treatment in the years following the run — including being exhibited in a dime museum in California — a groundswell of public support in Cleveland, Ohio, raised funds to rescue Balto and several of his surviving teammates, bringing them to a more dignified life at the Brookside Zoo.

Their arrival in Cleveland was celebrated with a parade and widespread community support, cementing Balto’s status as both an American icon and a beloved civic figure.

After Balto’s death in 1933, his preserved mount became a permanent exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where it continues to inspire visitors today as part of a century‑long legacy of survival, partnership, and resilience.

In recent years, Balto’s story has even contributed to scientific research: his DNA was included in comparative genomic studies published in Science, offering insights into the genetic diversity of sled dogs and how their unique traits inform broader understandings of mammalian biology.

Beyond Balto, historians and scholars acknowledge that the Serum Run was the work of many — teams of more than 150 dogs and numerous mushers, including the remarkable Siberian husky Togo, who covered the longest and most perilous stretches of the relay.

Yet Balto’s role as the lead dog on the final leg ensured his place in popular memory, and his legacy endures as a testament to teamwork, courage, and devotion during a moment of crisis.

Today, the centennial of the Serum Run is commemorated not just as a historical milestone but as part of Alaska’s cultural heritage, with events, reenactments, and exhibitions honoring the dogs and mushers who risked everything in the race against time.

The story of Balto and the Great Race of Mercy reminds us that sometimes the saviors of a community can come on four paws, guided by the instinct to persevere and serve — leaving a legacy that continues to resonate in museums, studies, and hearts around the world.

Balto’s journey from a modest sled dog to an enduring symbol of courage illustrates how acts of survival and compassion can echo across generations, highlighting the remarkable bond between humans and animals that endures long after the last mile has been traveled.