On a brisk autumn day in 1957 Moscow, a little stray dog weighing just over 10 pounds was scooped up from the busy city streets and thrust into history in a way no one could have imagined.

Her name was Laika, and although she had once wandered the sidewalks of the Russian capital, she would soon become one of the most famous — and controversial — animals in the history of space exploration. Her journey aboard Sputnik 2 made her the first living creature to orbit the Earth, but the price of that milestone was heartbreakingly high.

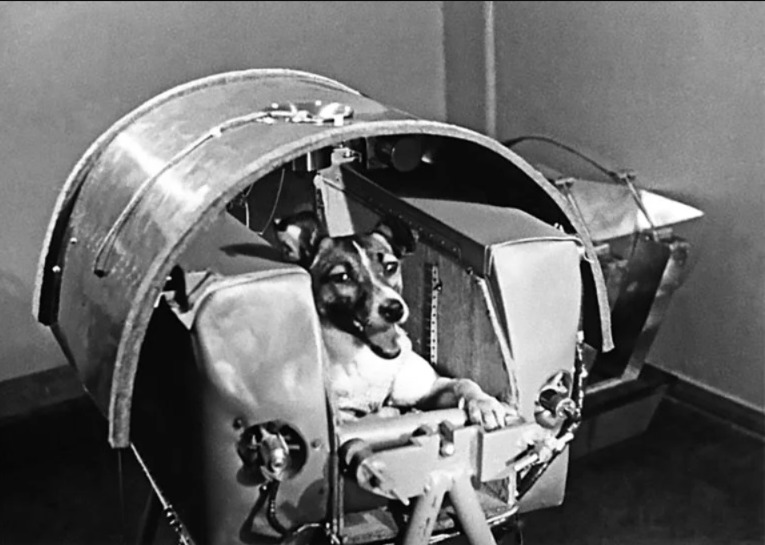

Laika’s selection came not because she was a trained astronaut or a champion of canine agility, but because she was small, calm, and considered suitable for life in a confined capsule.

Scientists at the time were eager to push the boundaries of human knowledge — especially amid the intense rivalries of the Cold War space race — and they believed that sending a living being into orbit could offer critical data about how biological systems respond to spaceflight before committing humans to the challenge.

Only about a month after being picked up as a stray, Laika was rigorously prepared for her journey. She and other “space dogs” were forced through confinement training, spun in centrifuges to simulate the forces of launch, and exposed to loud noises — procedures that would have been stressful for any animal.

Laika endured these trials alongside a few other dogs in training, including Albina and Mushka, before being chosen for the historic mission.

On November 3, 1957, Laika was launched into orbit inside the Soviet satellite Sputnik 2, marking an unprecedented scientific breakthrough: she became the first animal to orbit Earth. Initial Soviet announcements suggested she would survive in orbit for several days.

In reality, however, the technology to return her safely had not been developed, and no provisions were made for her survival or recovery.

The truth about Laika’s final hours was not fully revealed until decades later. In the early 2000s, a former Russian scientist acknowledged that Laika likely died within five to seven hours of launch — not from starvation or poisoning as previously claimed, but from overheating and stress caused by the failure of the spacecraft’s thermal control system.

Her tiny body, restrained in a cramped capsule and unable to move freely, was subjected to conditions that rising temperatures and panic responses overwhelmed.

Although her physical journey was tragically short, Laika’s mission circled the planet thousands of times before Sputnik 2 eventually disintegrated upon re‑entry into Earth’s atmosphere months later.

In a symbolic sense, she continued to orbit long after her life had ended — a poignant reminder of her place in history.

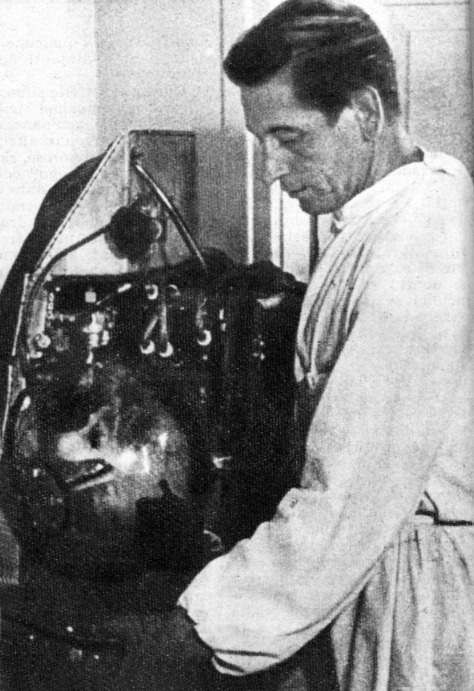

Laika’s story did not go unnoticed by her handlers. One of the mission’s leading experimenters, Oleg Gazenko, later expressed deep regret over Laika’s fate, reflecting that the decision to send her to her death was something even his contemporaries came to question: “The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it.”

For decades, Laika stood as a symbol of both scientific achievement and ethical controversy. Her mission offered early insights into how living organisms respond to the stresses of space, contributing to the knowledge base that would eventually make human spaceflight possible.

Yet the circumstances of her death and the conditions she endured raised ongoing ethical questions about animal testing and the treatment of animals in scientific research — debates that continue to this day.

Indeed, Laika’s legacy ultimately transcends the specifics of her mission. Her name became a rallying point for advocates pushing for more humane and non‑animal research methods, highlighting the moral complexity that arises when scientific curiosity intersects with the lives of sentient beings.

Campaigns and discussions inspired by her experience helped spur shifts in scientific funding priorities toward alternatives that reduce or eliminate the need for animal subjects.

More than six decades after she was launched into space, Laika’s story still resonates. Her journey was both a milestone in human exploration and a stark cautionary tale about the sacrifices demanded by scientific ambition.

In remembering Laika, we honor not just her pioneering role, but also confront the enduring challenges of balancing innovation with compassion — a lesson that continues to shape how we approach science and ethics in the years that follow.